Jan Kristian Haugland wrote a computer program to generate all 5-piece dissections of a 7-square to a 2-square, a 3-square, and a 6-square. Some of them are quite elaborate. Take a look at his webpage "dissection puzzles".

Katharina Huber pointed out that the roles of x and y are reversed when reducing Fibonacci's formula to Diophantus's formula on page 73.

In Sam Loyd's biography on page 73, I wrote that "Loyd popularized the 14-15 puzzle." However, Loyd's claims about having invented the puzzle appear to be false. In a recent book, Jerry Slocum and Dic Sonneveld have documented the origin and spread of the puzzle:Jerry Slocum and Dic Sonneveld, The 15 Puzzle: How it Drove the World Crazy, Slocum Puzzle Foundation, Beverly Hills, CA, 2006.As a result of an extensive search in newspapers and magazines from the puzzle's first appearance in 1879, Jerry and Dic concluded that Sam Loyd did not invent the 15-puzzle. (See page 94 of their book for their conclusion, and page 11 to see who was probably responsible.)

Koji Miyazaki, Hirohisa Hioki, and Naoki Odaka pointed out a problem in the reference in the fourth and fifth lines from the bottom of page 75. It should state that Figure 8.4 closely resembles Figure 7.10, not Figure 7.5.

As suggested by Puzzle 8.3, the Penta class can include identities produced using nonintegral values for p and q. This observation also applies to the Penta-penta class.

There are two typos in the specification of Method 5. In the second line of step 2, the first expression should be y - q - 1 rather than z - q - 1 and the second expression should be y - x rather than z - x.

(These are corrected in the paperback edition.)

More information on Henry Dudeney's life can be found in:Angela Newing, "Henry Ernest Dudeney, Britain's Greatest Puzzlist", in The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eugéne Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics and its History, edited by Richard K. Guy and Robert E. Woodrum, pp. 294-301, Mathematical Association of America, 1994.

When David Singmaster generously shared with me copies of Henry Ernest Dudeney's columns from the Weekly Dispatch for a 20-year period, I was floored to hold them in my hands. Not only because those pages were somewhat massive, but also because it opened up for me a tunnel into an amazing era a hundred years ago. I was fascinated to see how an ingenious man had established himself as the ultimate authority on mathematical recreations during his time. Usually, Dudeney would introduce a puzzle on a Saturday, give his readers a week to send in their solutions, and then announce a week later his own solution, along with the list of those correspondents who had supplied a correct answer. He would award a half guinea amongst a few of the correspondents who had sent in the best solutions.

As I studied this stack of raw data, I was especially struck by how Dudeney had handled the puzzle of dissecting an equilateral triangle to a square in as few pieces as possible. At the end of the two-week period, Dudeney announced that only one competitor, C. W. McElroy, had gotten at "the heart of the mystery." Dudeney explained an inferior 5-piece solution and gave his correspondents an additional two weeks "in order that readers may have another look at it." This was such an extraordinary circumstance that, upon further thought, I wondered if Dudeney had actually known about the 4-piece dissection before he opened up the letter from McElroy during the initial two-week period. Perhaps Dudeney felt that he did not understand McElroy's solution well enough to explain it.Exploring this possibility, I ended up writing a series of six "mini-chapters" for my second book Hinged Dissections: Swinging and Twisting, entitled "Curious Case," parts 1 through 6. In part 4, "A Dudeneyan Slip," I compared Dudeney's discussion in the Weekly Dispatch with his revised presentation of the puzzle in "The Haberdasher's Puzzle" in his final installment of his puzzle series "The Canterbury Puzzles," which appeared in "The London Magazine," in 1903. The haberdasher had challenged a group of Canterbury pilgrims to cut an equilateral triangle to a square in four pieces, while he himself did not actually know of a solution in any number of pieces. Was this a hidden allusion to Dudeney's having posed a puzzle for which he didn't know the best solution? I gave a plausible analysis of the circumstances, an analysis that probably has annoyed some Dudeney enthusiasts!

Using Method 2C, I gave 5-piece dissections for all squares in the PP-plus class. One solution in the PP-plus class is 92 + 22 + 62 = 112, for which L. P. Mochalov gave a 5-piece dissection in Vladimir Belov's 1992 book. (See the updates to chapter 1.) Mochalov's method can be generalized to handle all squares in the PP-plus class.

I should have written Cossali's name as Pietro Cossali.

There is another way to produce Cossali's class without resorting to the device of n=m or n=p, as I did in the book. Instead, take p, q, and n all to be 1, and take m to to be odd. This will give values that have a common factor of 4. The values are then in a different order from what you see on page 84.

David Eppstein (at the University of California, Irvine) has pointed out that Robert Reid's 5-piece dissection of 4-square, 9-square, and 48-square to a 49-square in Fig. 8.19 is not an isolated dissection. Instead, it belongs to a class whose first four members are (1, 2, 2, 3), (4, 9, 48, 49), (21, 50, 1470, 1471), and (120, 289, 48960, 48961).

Members of the class are integral solutions to the simultaneous equations:x (z +1 - y - x) = (x - 1) z

z + 1 - y = (y - 1) (y - x)

x2 + y2 = 2 z + 1

w = z + 1

All solutions to these equations can be found by the following method. Consider a series of pairs of values ai,bi satisfying:a1 = b1 = 1

ai+1 = ai + bi

bi+1 = 2ai + bi

We can prove by induction that:(b2j)2 = 2(a2j)2 + 1

(b2j+1)2 + 1 = 2(a2j+1)2

Let y2j = (b2j)2 and y2j+1 = (b2j+1)2 + 1. Then take xi = sqrt(yi-1(yi-1)).

It follows that zi = xi sqrt(2yi(yi-1)).

Thus the values of xi, yi, zi, and wi satisfy the requirements for Reid's dissection.

Note that bi / ai is an approximation for the square root of 2, which is generated by the continued fraction technique for solving the Pell equation b2 + 1 = 2a2. About 130 A.D. Theon of Smyrna gave the recursive formulas for ai and bi. They had earlier been given in geometric form. (See page 341 of Dickson (1920).) Thus I will call this class of solutions to x2 + y2 + z2 = w2 Theon's class.

Since the 5-piece dissection for this class uses two steps, and the steps are specializations of P-slides, the existence of this class suggests a relationship for three squares to one that I missed in chapter 4. Squares for that relationship will have 7-piece dissections.

I identified many dissections of three squares to one that use just five pieces, and also gave one dissection of four squares that uses six pieces. In 1978, A.J.W. Duivestijn published a set of 21 squares of different sizes that can be rearranged without cutting to form a single square. This leaves open the problem of dissecting n different-sized squares, for n between 3 and 21, into the fewest number of pieces that form a larger square. Another optimization criterion is to minimize the total length of the cut. Joe Kingston and Des MacHale investigate this latter problem in their article, "Dissecting Squares," which is to appear in the Mathematical Gazette in November 2001. Since submitting their article, they have found some improved results, which they describe in "Some Improved Dissections of Squares."

In the Mathematical Gazette, Vol. 52, Issue 381 (October 1968) p. 273, Classroom Note 172 responded to a conjecture in Note 153, namely that the sum of three consecutive squares, with the smallest square greater than 9, can be expressed as the sum of three different squares. R. Goodall, a student from Nottingham College of Education, in Clifton, Nottingham, United Kingdom. claimed that the assertion held for three different groups of solutions, Groups 1, 2, and 3.

In April 2019 I found 7-piece dissections of squares that evidence these relationships, parameterized for every integer n > 0:

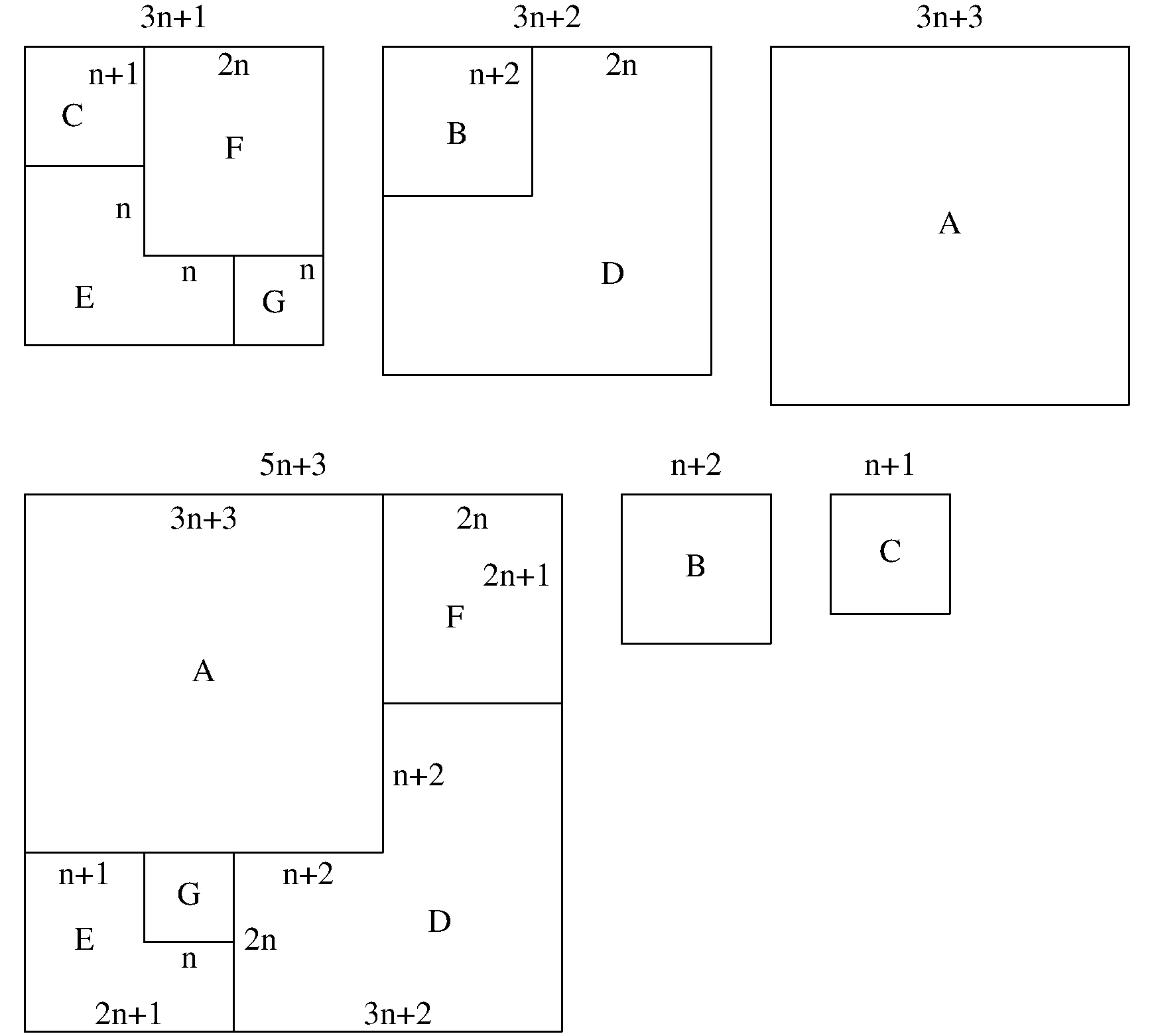

(Group 1) - for any positive integer n, where (3n+1)2 +(3n+2)2 +(3n+3)2 = (5n+3)2 +(n+2)2 +(n+1)2

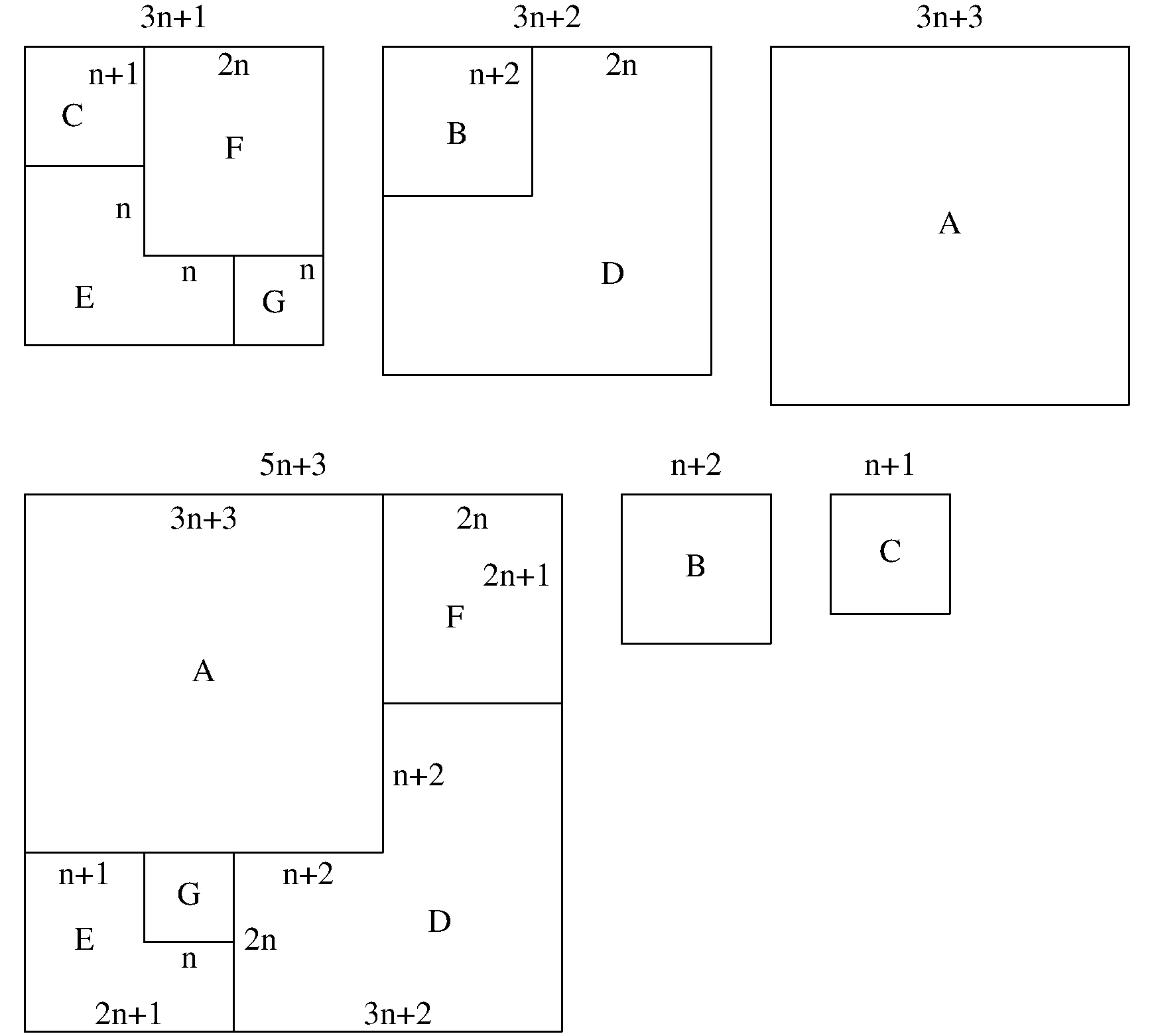

(Group 2) - for any positive integer n, where (3n+2)2 +(3n+3)2 +(3n+4)2 = (5n+5)2 +(n+2)2 +n2

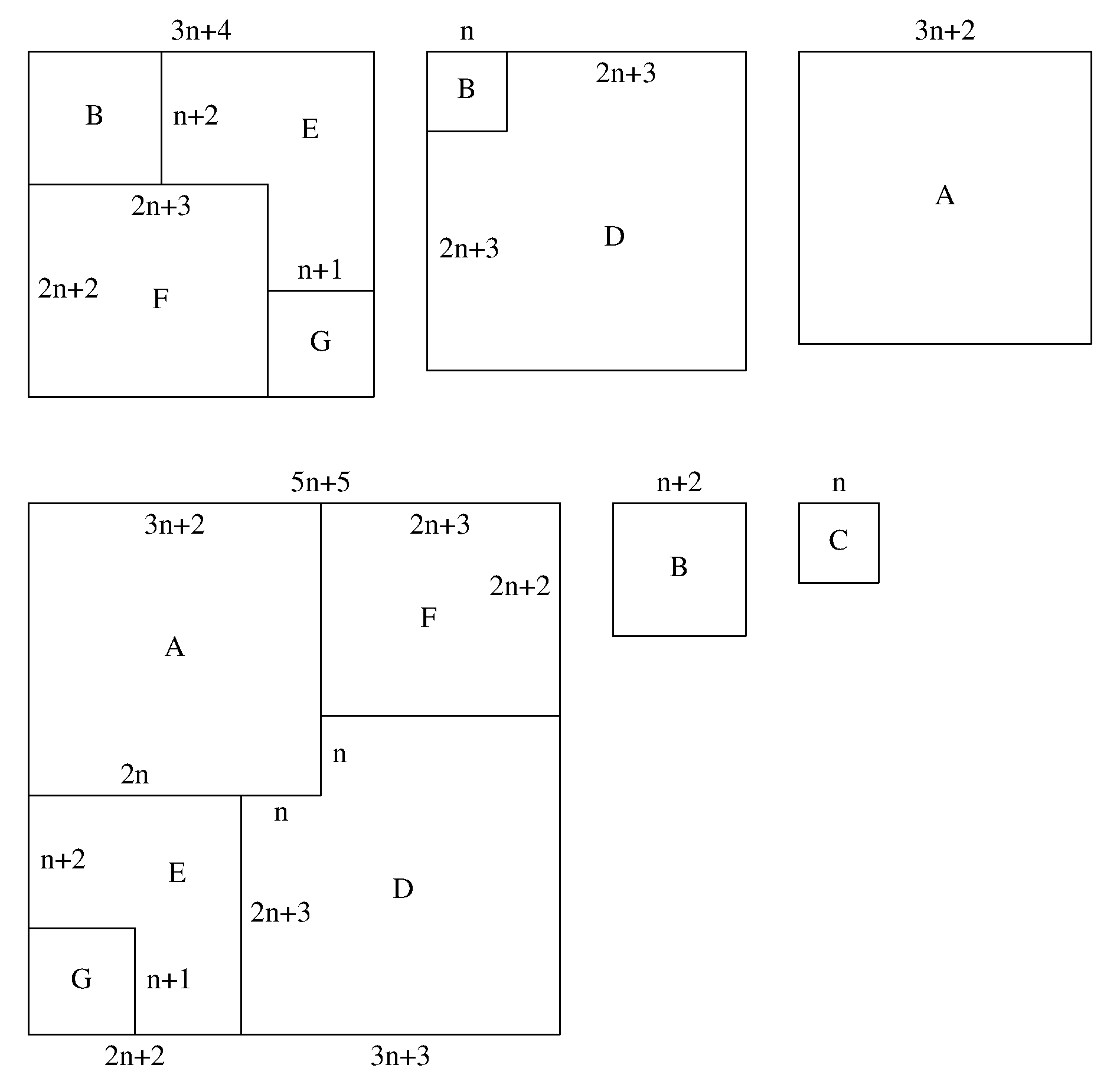

(Group 3) - for any positive integer n, where (3n)2 +(3n+1)2 +(3n+2)2 = (5n+2)2 +n2 +(n–1)2

This is reminiscent of chapters 7 and 8 in my book Dissections Plane and Fancy, in which I discussed methods for dissections of squares for Pythagorean triples, for dissections of two squares to two squares, as well as three squares to one square. Of course, we would expect a richer set of identities with three squares on the left-hand side of the equation and three squares on the right-hand side of the equation, even with the restriction of consecutive integers on the left.

Copyright 1997-2019, Greg N. Frederickson.

Permission is granted to any purchaser of

Dissections: Plane & Fancy

to print out a copy

of this page for his or her own personal use.

Last updated May 3, 2019.